Intro to Computer Engineering

Studio 1 - Programming and Bit Manipulation

Click here to access the Canvas page with the repository for this studio.

Introduction

Now that you know the basics of the Arduino IDE and its Programming Language, it’s time to go a bit more in-depth about how it and computers in general work.

The C Programming Language

If you took CSE131 or AP Computer Science, you should already be familiar with Java. We will still use a lot of Java in this class, but we’re also switching the emphasis to another language called C.

We do this for two reasons:

- You program Arduinos in C

- C is much closer to the hardware

Unlike Java, which runs on a virtual machine on top of your existing operating system, C compiles to pure machine language: the direct instruction set that your computer actually runs. In other words, if you’d like to see the exact instructions your computer uses to draw a pixel onscreen in a video game or download your email, you look at a compiled C program.

Lucky for us, uncompiled C (like, C code) looks a lot like Java. So much so that you should be able to read C with no problems.

Compiled code is a different story. We’ll deal with the human-readable “rendition” of machine-language, Assembly, later in the semester, but for now we’ll deal with the more immediate problem of how programs interact with the computer

Studio Proper

Information representation

But before we can ever talk about I/O (input/output) and programs and compiling things, you need to understand how the computer stores data. In other words, before you can understand how computers manipulate data, you must know how they represent it.

To that end, we’ve prepared some pen-and-paper exercises to get you thinking about data like a computer does.

If you are having trouble with the concepts behind any of these questions, try reading Chapter 8 in the course textbook or look through the Guide to Information Representation.

Binary & Bases

Binary is what every form of data on your computer eventually boils down to: some chain of HIGHs and LOWs, zeroes and ones. These questions will explore your understanding of binary as a base 2 number system.

The subscript on a number indicates its current base. If no base is given, assume base 10.

- What is 10102 in base 10?

- What is 6810 in binary?

- What is 2010 in base 6?

Hexadecimal

Hexadecimal is base 16. It ends up being a very nice way of representing computer-related numbers because it jives with binary so well.

- What is 1010 01012 in hexadecimal?

- What is 0xF1 in binary?

- How many digits of binary correspond to a digit of hex?

- Hex uses the letters

AthroughFto go up to base 16. What is the highest base we can represent if we use all the letters of the alphabet?

If possible, have a TA check your answers before moving on

Bits of Arduino

Both the Arduino IDE and your Eclipse Workspace should be set up before starting this section (see Studio 0 for help).

Setup

- Create the studio repository (link is at the top of the page)

- Open

bits.ino(bits / bits.ino) - Connect your Ardunio to the PC

- Check your port

Bit Dissection

Run bits.ino in the Arduino IDE, opening up the Serial Monitor after it is done uploading.

In the Serial Monitor you will see the number 100 written in Decimal, Hexadecimal, and Binary. You will also see what the number looks like after a LEFT-SHIFT, RIGHT-SHIFT, and INVERSE.

- Look at the Binary Representation

- what does

LEFT-SHIFTdo? - what does

RIGHT-SHIFTdo? - what does

INVERSEdo?

- what does

- Change the Variable

a

void setup() {

unsigned a = 100; //Change this number

unsigned b = shiftLeft(a); //Leave these alone

...

- Try running the program with a few new values (be sure to Upload it after any changes)

- Try to find patterns and describe them. (Ex: If you know what happens to 5 due to all three operations, what happens to 10?)

- Try more values to validate your patterns

- If you haven’t already make

agreater than32768- Do any of your patterns break?

- What happened when you used

LEFT-SHIFT?

What are the implications of overflowing in a program? What are some ways to avoid OverFlow?

FSMs

Here is a great introduction to FSMs. They are also described in Chapter 7 of the text (read Section 7.1).

For the final Part of the studio we have designed another program FSM.ino, a simplified binary counter, designed to introduce you to the concepts and syntax of FSMs that you will need for Assignment 1

- Open

FSM.ino(FSM / FSM.ino) - Upload

FSMs.inoonto the Arduino - Open the Serial Monitor and notice how the state changes with the Binary Counter

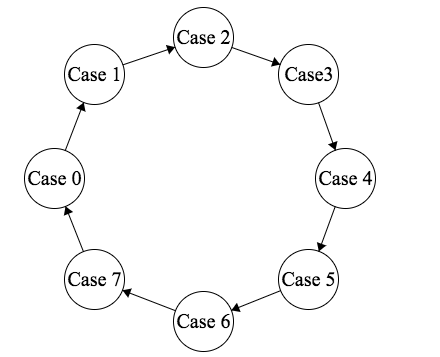

Here is a Visual Depiction of the FSM:

- The circles represent the possible states the machine can be in, and each circle has its own set of instructions.

In the studio example Case1 would have instructions to print out

1 : 001. - The arrows represent the possible movements the machine can make.

In the studio example the arrow from Case1 to Case2 shows that a movement from 1 to 2 is possible.

- This particular FSM can not move backward or even stay in the same state because the arrows only point forward

Enums

Here is this FSM’s enum:

enum State {

up0, // 0

up1, // 1

up2, // 2

up3, // 3

up4, // 4

up5, // 5

up6, // 6

up7, // 7

};

State counterState = up0;

What does this Output:

state = up4;

Serial.print(state);

Enum types in C are just numbers with readable names, and those names are not compiled into your program – meaning “up4” is not accessible at runtime. In other Languages, however, Enums sometimes have a toString() or name() method that will allow access to a name at runtime.

An Enum is useful when a variable can only take one out of a small set of possible values. Examples include Months, Game Pieces, or the Cardinal Directions.

A great way to think about these are Drop Down Selection boxes:

](selectBox.png)

There can only be one selection from Multiple Choices

enum Fruit {

Banana,

Apple,

Mango

};

Fruit myFruit = Banana;

switch(myFruit) {

case Banana:

print("Banana Selected");

break;

case Apple:

print("Apple Selected");

break;

case Mango:

print("Mango Selected")

break;

}

Switch Statements:

switch statements are where enums shine.

Here is the Switch statement from the Example:

switch(state){

case up0: //When state up0 , the FSM must:

bit1 = 0; //set the bits to match the Count

bit2 = 0;

bit3 = 0;

pprint(state);

state = up1; //Move to the next state

//The next loop will go to case up1

break; //Break to the end of the switch

//So the next case won't run too

case up1: //only if counterState == up1

}

Advanced FSMs

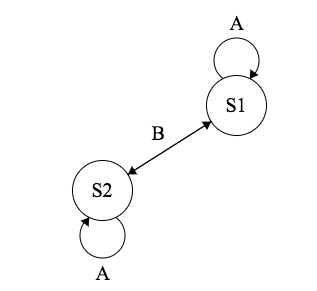

Here is an example of an FSM that can both switch and remain in its own state depending on the Input:

- Input A : stays in own state

- Input B : switches state

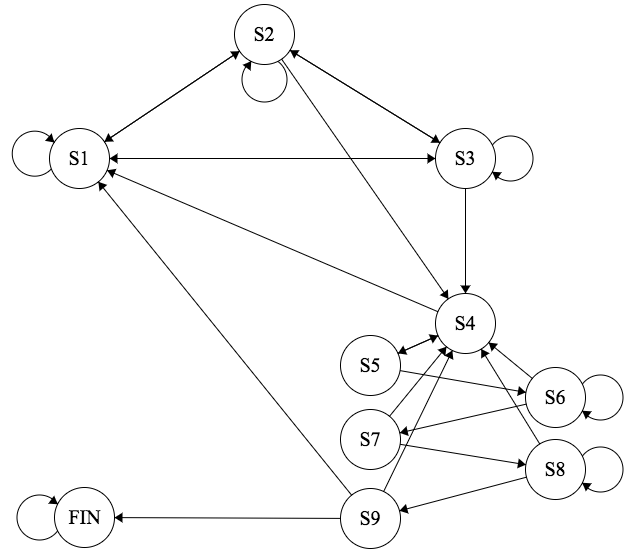

Things can can get Confusing Quickly:

Go through Key Concepts in your head to make sure you have all that you need to start on Assignment 1. As always if you think you missed a concept or just want a wonderful TA to explain it to you Please Ask (it’s their job)

Check out!

- Commit your code and get checked out by a TA.

Key Concepts

This is a checklist for you to see what the Studio is designed to teach you.

- Binary, Hexadecimal, and other Bases

- Bitwise Operations

- LEFTSHIFT

- RIGHTSHIFT

- INVERSE

- Overflow

- FSMs

- Cases

- Enums

- What happens at Runtime

switchbreak

- Repository

- Eclipse

Team > commit

- Eclipse

Generated at 2024-07-01 15:58:42 +0000.

Page written by Claire Heuckeroth, Ben Stolovitz, and Sean Schaffer.